Cutting Down Culture

Following up on the last piece published here, we move from mediocrity to its sense of entitlement. This tends to be cast by culture sector actors as a “crisis” of some sort. Here, it will be concretely tied to recent forms of protest about the state and status of art. In one case these questions have been pragmatically addressed; in the other, they are more open-ended. I will discuss this in terms of the nature of concrete demands and by examining the appearance of how this “crisis” has been constructed as a visual spectacle (such as it is).

The spectre of a crisis for the arts has been almost perpetual. I cannot recall a time in my life when the advocates of culture were not fulminating on the issue, typically with far more ambivalence and variety than has come to be the case. The arts in Canada have seemingly always been in crisis mode.

Sticking strictly to what has occurred within this city, it is useful to contrast what will be discussed below to the past. In the 1970s, the artworld’s crisis involved some (compared to what exists now) large demonstrations that included public nudity, live animal sacrifice, obscene chanting, raiding various events, occupying buildings, and so on. These “poetic” events, usually proclaimed as such and placed in the lineage of Automatism, soon gave way to a lot of less spectacular bureaucratic maneuvering. To the degree that they persisted, it was in increasingly rote formations.

Lately, two groups have been getting some press as arts advocates, their material circulating within the social media and exhibition spaces of various galleries and artist-run centres in the city. One is the Grand mobilisation pour les art au Québec (GMAQ), a loose and unofficial “movement.” The older of the two is the Front commun pour les arts, a more traditional arts advocacy campaign affiliated with specific organizations and institutions.

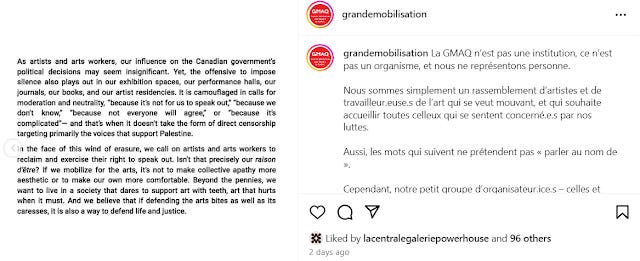

GMAQ is not actually an organization, does not represent anyone, has no direct goal but has a vague sense of doom and moral panic. This is quite different from established organizations such as COVA/DAAV, which largely exist to police things like copyright and control the flow of images. At the back of such operations is the concrete political ambition that has tended to historically animate arts advocacy, which is not about the romantic transformation of the world so much as establishing a standard of professional status. One of the original members of CARFAC used to argue that the aim of groups like that was to make artists the equivalent of public school janitors and have them compensated accordingly.

It is more in line with this type of practical advocacy that the Front commun exists. A PR statement reads

A number of organizations have joined forces to create the Front commun pour les arts, dedicated to the long-term survival of Québec culture. The 17 organizations are calling on the Québec government, through a communications campaign, to shout loud and clear that ‘Our culture deserves better than to be cut down.’ All are sounding the alarm, and calling on the Legault government to act before too many cultural organizations suffer the consequences of the Conseil des arts et des lettres du Québec’s (CALQ) under-investment.

They have cited a rolling reduction in budgetary allocations to CALQ over the past several years, falling from $185 million in 2022-2023 to $160 million for 2024-2025. Over this period, “the average support offered to organizations supported by specific programming fell by 35%.” Grants requests last year exceeded CALQ's budgeted capacity by 61%.

In light of these and related challenges, the Front commun pour les arts is calling for the CALQ's permanent funding to increase to $200 million; budget consolidation to help ensure permanent funding; and the indexing of CALQ’s programmes.

In January, Regroupement des centres d’artistes autogérés du Québec (RCAAQ) denounced the “precarious” salaries of artist-run centre functionaries. These concerns have been lumped in with more general panic in the cultural industries over funding. Around 300 “artists” (what this entails is unclear) were the signatories of an open letter that was published in La Presse. Collectively, they called for an “états généraux” on culture. Central to their concerns are salaries and a complaint that the average artist in the province only made $20,787 per annum.

These considerations have been combined with calls for greater attention paid to the regions in a bid to make sure that “Québec culture remains an economic sector that benefits all of Québec society.” What that means is unclear. Speaking of the cultural sector as though it is a coherent professional group barely makes sense, especially in economic terms. As Minister of Culture and Communications Mathieu Lacombe pointed out, “The risk is that we end up with people who have very different realities. Music has nothing to do with theatre, and dance has nothing to do with audiovisuals.”

Even on the level of industrial tags, this is confusing. An artist may be a cultural worker but a cultural worker is not necessarily an artist. Producing art is not necessarily the same thing as producing culture and so on. You can make a good argument that most of this is not art at all, that it is “culture” and “culture,” as one leading bureaucrat insisted, is mostly the enchantment of the political economy of the state. “Artists” or “culture workers” are titles that apply to quite disparate things from television actors to painters to a slew of bureaucratic functionaries, each of which involves extremely different costs and audience sizes.

According to the Front commun, the most substantive cost that these funding reductions could have on the public is purported to be a weakened cultural sector, whose primary services involve things like “mediation and audience development activities.” While some of the issues they advocate for are straightforwardly defensible (lack of funding means reduced support for emerging artists and likely reduced international competitiveness), others are much more questionable.

It is certainly the case that there has been significant inflation and cost increases in many of the things involved in the production of art. Likewise, it is true that there have been significant decreases in the cost of many technologies and for the non-traditional venues in which to show art. The often retrograde insistence on brick-and-mortar art venues seems rather old-fashioned for something that tends to pitch itself as looking toward the future and internet property is extraordinarily cheap in comparison. A great deal of arts funding advocacy is oriented around preserving and expanding institutional models that are likely no longer the best servants of art. It may be that defunding artist-run centres and allocating those funds to other things may be a better use of them.

While it no doubt means more to people’s careers to show in traditional galleries and art spaces, what this does for the art itself varies enormously. A show at Galeries Roger Bellemare et Christian Lambert always looks much better in person. The same cannot be said for one at McBride Contemporain or Hughes Charbonneau (the opposite is usually true). Shows at the artist-run centre SBC are so consistently aesthetically vapid and perfunctorily curated that visiting them is more of a disservice to their already underwhelming ad copy than anything.

Perhaps the more striking thing is that the visual arts have been defined by the Front commun as a “niche discipline” which would somehow suffer a “decline in artistic daring” if they received less funding and were less tightly indexed to ongoing state programming. It is not remotely evident (and likely cannot be proven), that state-sponsorship has resulted in “better” art, whatever one takes that term to imply. It has resulted in more of it within a very specific set of traditional outlets.

As Durand’s ambivalent account of the history of the province’s artist-run centres clearly suggests, the results of this structure of patronage (it is notable that this is not typically written of as patronage by its apologists but simply as a kind of social funding that makes art equivalent to health care, that great morbid symbol of provincial mediocrity) very rapidly became a stultified, predictable set of generic art practices that were entirely devoid of artistic or conceptual daring. It is not increased funding that would change this since these failures are primarily the result of the political norms of the sector, and which its advocates wish to further entrench.

It should be noted, since it never is, that arts funding is expropriation through totalitarian violence which, in the Canadian case, is explicitly for the sake of the promotion of state theology (“enchantment” or the fantasy of “cultural humanity”).

If the Front commun provided a relatively concrete if not especially clear example of arts advocacy, the following does not.

GMAQ started last spring in the theatre sector with demonstrations. It has since become more of an interdisciplinary matter. The general impression is one of blandness. This applies both to the fairly consistent visual language that has been used, the various gatherings that they have documented, and the rhetoric that they employ. It tends to come off as sterile.

On October 5, they held a “day or reflection/action” at Fonderie Darling. 30-40 people gathered (Le Devoir reported 30 but official social media claimed 40) for this event, several in orange vests (apparently an allusion to the yellow vests of France). They broke into groups where they discussed various ways of justifying action and actions to take. I did not attend but from what the organizers have bothered to publicize, evidently this involved them reading canned statements about Gaza. The newspaper coverage ran with the more spectacular idea of a general strike, but what would that mean for visual artists, who barely even show their work for the most part?

Although strikes have all sorts of romantic old-school labour fantasies attached to them, most strikes in Canadian history are things like civil servant and teacher’s strikes, the two groups of people probably the least meriting increased compensation in the country. No one will institute back-to-work legislation against fibre arts graduates.

One of the public facets of this group has been to circulate cartoons lampooning stereotypes about the arts, specifically, the notion that they are socially useless. Cultural workers, however, cannot be “useless” because they are functionaries of the ideological state apparatus. RCAAQ seems very proud of this status and has celebrated itself as such. This also means that as a practice, a “strike” would only be a break on further ideological reproduction, which might be a positive thing. As practice, however, it is likely to be played in the opposite direction, as a means to further consolidate this reproductive function. If the basic logic of “culture” is performative, is a “strike” simply an end to performance, or is it just another variety of performance, a non-compensated demand for expanded compensation? This is what the various “actions” that have been taken so far tend to suggest.

Appropriately, this ties into some of the most basic thematic issues that these vague protests seem to raise. The dichotomy of invisibility/visibility (with the complementary term erasure) and the dichotomy of mobilization vs apathy seem to be the basic dramatic terms of reference that have been called up. What is going on strike if not making inactivity paradoxically active as the visible? The most recurrent symbol for this over the past few months has been the circulation of a cloaked monument. This image associated with GMAQ has a loose resemblance to the cloaked figure of the grim reaper being circulated by Front commun.

If strike action for the cultural sector seems comical (and has been performed as such with protesters appearing in tutus at a recent public gathering), this is doubled by the cartoonish spectre of the arts being struck down by the decline in funding. Unlike in good satirical or polemical imagery, there is not even much of a hint of historical specificity to any of this. Why this weirdly Gothic imagery of masked grim reapers from 60s horror films and statues that are covered? This is particularly striking given the hostility to monuments that has been showing up recently in protest-themed shows like this or this. There is also the other irony that a massive monument covered in a tarp does not exactly make it invisible so much as cloak it in an aura of significance that the artwork probably does not possess. This mystical power of art, referenced obviously in some of the work of Duchamp or Christo, suggests that art benefits more from not actually being encountered, that its power is its anti-social quality.

Most of the visual identity of GMAQ has been the product of the propagandist/cartoonist Clément de Gaulejac. There is not a lot to say about its identity. It is extremely simplistic, flat, utilitarian, sans serif with balloon letters (but not too inflated), and has all the originality of a piece of free clip art. Presumably, this is all intended to function as a means of easy communication, but the results are murkier than that.

To take the most recent example. “This week, Clément dives into the tricky balance of equity versus equality. How do we decide how to distribute resources based on everyone’s (urgent) needs — because clearly, figuring out who gets what is as easy as herding cats in a rainstorm!”

Does a picture of a morbidly obese black cat licking its asshole while whining that it contributes to society say something about equity? Is the cat supposed to represent funding bodies? Is it equity or equality that is asslicking? If shit and food are equalized, what does this imply about distribution? If anything (and leaving aside the obvious “racist” interpretation it more blatantly suggests), it seems like a joke about the kind of people who take these sorts of issues seriously. Even in its most crudely caricatured and utilitarian form, art is useless at communicating anything.

While GMAQ claims not to represent anyone and to be advocating for open dialogue, they seem to have a pretty specific normative set of assumptions about what art is and does (they have to or none of this would make sense). Judging by their statements, it appears to be the assumption that art is not meant to serve “apathy” but be a kind of engagement and reclamation of protest that has moral functions for the sake of “society.”

In addition to giving the extreme vagueness of all of this some sort of moral gravitas, the exploitation of the “Gaza” trope dovetails with the thematization of “erasure” and symbolically conflates artists with Palestinians and a refusal to give them more money with genocide. This extraordinarily clunky gesture is almost grotesquely funny, but, while no doubt naively earnest (or very moronic), it also ends up foregrounding the degree to which it is an aesthetic spectacle that artists seem to have an inordinately philistine reaction to. (What the IDF has done to Gaza can legitimately be read as an innovative instance of Land Art or architectural intervention that is as much a form of state-sponsored art as anything produced by the Canada Council. This is not to imply any moral interpretation of it.)

The more curious thing amid all the histrionics and the generic sense of doom that replays almost identical rhetoric deployed last year around the biennial, is how basically aesthetically uninteresting it all is. Given that art is the issue, this should be a matter of some concern. In a way, the kitsch aesthetics of this whole debacle probably say something about the quality of the art in the city that they are trying to secure.