Reviews: Stéphane Gilot at Optica and Chromatopia at Fondation Guido Molinari

Previously, I have discussed my reservations around the employment of the role of “narrative” in exhibitions. Specifically, this involves the lack of clarity in how this notion translates to the visual display of work and how interaction with the work actually operates. Unless you stretch the term to its breaking point, very little in the practical visual logic of most exhibitions has any strong narrative content. This just seems like an unnaturally appended term to appeal to concepts that can then (presumably) be projected onto the work when it is not clearly evident. As such, it allows for the set-up of a fantasy of relations that the material reality of the work demonstrates to be absent. As a strategy, it is a way of trying to smuggle things in without doing the work that would make them sensible as visual art (if they can even make sense that way). So, an appeal to narrative is primarily an authoritarian device of enframing, something that tends to be the reserve of curating (whether by the artist-as-curator or the curator-as-artist).

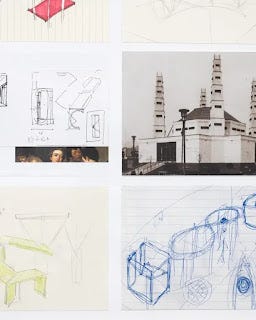

Stéphane Gilot’s L’orbe dérobé (Atlas des possibles) 30 ans de pratique de dessin, performance, architecture is in one of the gallery spaces at Optica. It consists of framed drawings and collages that dot the walls and several softly coloured objects that sit in the centre of the space. Images of these objects appear in sketches, texts, and other forms within the frames. The viewer is expected to go back and forth between the different displays to mix and match things. Much of this has been harvested from various performances undertaken by the artist, tying it to the general propism generic to so much Contemporary Art practice.

According to the accompanying text, the exhibition gathers drawings

...into collage charts, assembles personal archives and reactivates them in non-chronological and nonlinear combinations. These groupings reveal the constancy of certain details but also their transformation and reinterpretation over time, as well as completed or imagined projects. The series Éloge des nuées, dedicated to various natural, astronomical, or fantastical phenomena, is an inventory of celestial apparitions. The association between different elements—weather events, flying machines, forms and architectures drawn from science fiction or visions—creates a metanarrative that underlies all of Gilot’s work. Each project becomes a theatre of apparitions, a space of projection, in which a new configuration of the inventoried components can emerge. The sculptures in the exhibition act as another kind of catalogue, an index of elemental forms that keep resurfacing in architectural interpretations, installations, models, and watercolours. Like clues, these geometric volumes infiltrate the atlases, then reappear in large drawings

Even with all this overtly theatrical framing, however, the whole thing feels far more like one of those toys that children play with where they have to figure out which three-dimensional shape can fit in which hole in a grid. (This, for instance, but there are many variations). These are largely intended to teach children to recognize shapes and do some basic hand-eye coordination activities. This sort of pre-kindergarten activity is the heart of the show and its variety of propism.

In the context of playing with a toy, this function of activity is pretty straightforward. It becomes a little less so when dealing with art exhibitions. What the use of the space, the arrangement of objects, and the general framing of play foregrounds is the ease of the game. While “open” as far as significance goes, the projection of significance onto the objects does not follow as neatly as the mixing and matching of shapes and colours to one another. Although the PR release insists that this game is potentially “infinite,” it quickly becomes clear that this is not the case. It is less convincing as a matter of “metanarrative” than a game with unclear rules and no discernible narrative.

Pretty soon, once the basic matching is done, it becomes a rather different kind of game. It is not a puzzle since they have a definite end. Instead, it becomes an exercise in the increase of vagueness. The initial matching game gives way to the fuzziness of relations between the various images and each other, or the shapes at the centre. Predictably, this is framed in terms of “narrative,” but it seems to be the failure of anything like a narrative to be plausibly articulated. (Maybe the supplemental appeal to narrative is just a tool to exacerbate this process, which is more interesting than, and very different from, narrative condensation). The game eventually roves from the matching of the highly articulated to this exponentially increasing process of disarticulation.

Equally playful, albeit in a less mechanistic way, the residence/exhibition Chromatopia at Fondation Guido Molinari is the work of Jean-Maxime Dufresne and Virginie Laganière. The two artists have been working together for twenty years. Here, they combine photos, video, sculptural elements, etc., to create a set of spaces distinguished by the dominance of key colours and the different levels of visual and object density.

Works span from sitting on the floor to being placed near the high ceilings and provide extensive, erratic positions that the eye has to continually adapt to (unlike the fairly reductive and streamlined gridding in the Optica exhibition). The various dividing walls of the space have been moved around to create an optimal level of spatial differentiation which is highlighted by the use of colours applied to them. Plinths and other support devices are employed to introduce more scalar distinctions and give the appearance of the show a higher sense of relief that complicates the blocks of colour that appear on many of the walls. These are broken up by photos bearing close tones to those of the block. In some instances, coloured light is also introduced, providing an immersive colour saturation which alters the function of the visual objects.

According to Camille Bédard’s accompanying text, the artists

…have turned their residency at the Guido Molinari Foundation into a project investigating the polysemy of colour. […] With their exhibition Chromatopia, they examine the territories of color, its anthropological, social, historical and political dimensions, as well as the imaginary it inspires. […] True to their artistic practice, following a methodology combining documentation, scientific research and fictional narratives, Jean-Maxime and Virginie met with a sociologist, neuroscientists, entomologists, art theorists and a specialist in optical physics.

The expansive framing that the operations carried out by the artists, at least as outlined in the exhibition text by Bédard, suggests some overlap with something like Michel Pastoureau’s book Bleu: Histoire d’une couleur (2000). In that text, Pastoureau sought to write a social history of blue, which effectively meant charting it across numerous continents and periods and indexing it to localized systems of meaning (that shifted dramatically, even over brief periods) and the ambiguities that arose from even apparently stable meanings when a coloured object was put to use. It also indexed the colour to changes in exploration, exploitation, and concomitant developments in markets.

In a narrative such as Pastoureau’s, blue effectively functioned as an alibi for organizing an array of theoretical clichés, citations, and inherited concepts which became seemingly naturalized in the process and blue provided the illusion of continuity. The flaw of the book was mostly that it did not really come to grips with the way that chroma relativized these other, more readily commodifiable conceptual frames, and that the colour clearly had an autonomous history that seemed very different from the more familiar human stories that caught the author’s eye. He settled, as the Bédard’s accompanying exhibition text notes, for conceding that colour was indefinable and rebelled against analysis.

In her text, we are also told that “[I]n a bid to decentralize the anthropocentric perspective on the question, [the artists] have initiated a collaboration with the Insectarium de Montréal to observe and better understand the biological function of color in insects, particularly in butterflies.” This is one of the substantive ways that their work intersects with that of Molinari. In a bid to liberate vision from “anthropocentrism,” however, the study of insects works more as a kind of conceptual voyeurism for an alternative way of seeing to be imagined (but likely can not be biologically experienced by a human viewer). This can be opposed to the more direct way that the Plasticiens attempted to harness the apparatus of vision in a way that is closer to working on fundamental neural hardware in a non-cognitive way. The first strategy (Dufresne and Laganière), is more about the simulation of a fantasy, and the second is about a non-fantastic stimulation of unintentional phenomena.

Molinari and his colleagues (Les Plasticiens) attempted an array of strategies that largely came down to different types of pictorial reductionism that would allow for chroma to be radicalized. Molinari’s work, which was consistently concerned with the conceptualization of painting as an optical event, one that was accomplished through the elimination of gesturality and a reliance on seriality (at least in one period of his career) tended to use bands of colour set side by side to vibrate and give the picture its dynamism. This contraption, a product of masking tape and rolled industrial paint, resulted in some of his best-known work.

One example of this strain of his work is included in the exhibition Sériel ocre-rose (1968). Placed in the vault area, the painting is subjected to different colours of light by Dufresne and Laganière. The shifts in light do cause significant alterations to how the painting is perceived. Their intervention largely consists of this spectacularization of perception, which is done here in a simple but effective way. This also marks out one of the major differences between what Molinari did and what they are doing. Basically, this marks a shift from the type of experiment on the viewer that Molinari’s work directly enacted and the experimental pedagogy that the two artists are trying to create here. In the instance of the installation in the vault area, the overlap between the two things mostly works, and the strong foregrounding of the demonstrative function of the exhibition as a sort of eye test is clear. The rest of the time, it is less so.

Most of the exhibition comes down to another instance of mix and matching, only using colour rather than shape as the show at Optica did. Again, we are prompted to project this into metanarratives (of the various disciplinary discourses that are alluded to and (loosely) pictorially referenced). Still, there is not enough information visually present for that to work. There is also no drive to excessive projection as there was in the Optica show. Colour keeps everything on a surface level of recognition and this is less an invitation to narrative or conceptual fantasy than a matter of design.

When the bulk of the exhibition works, it works by rhythm and contrast, both in terms of colour concentration and placement. Inversion is a significant part of this and it highlights the extent to which the geometrical design of the space makes up most of the content. The “content” within the images themselves recedes, leaving only surface colour and shape. Accent spaces, colour blocks, and so on, all stress the projective and surface aspects, leaving little room for pictorial sense. When this is less effective is when the pictorial is given too much weight.

* All images from the social media accounts of the galleries.